When Australia voted No in 1999

What Australia's rejection of a republic at a referendum can teach us about politics and media

On November 6, 1999, Australians voted in a referendum on our nation’s constitution. The choice was between remaining a constitutional monarchy with Queen Elizabeth II as head of state (in common with Britain and 14 other countries currently) or becoming a republic and severing a symbolic link with Britain. Both the campaign and the outcome were remarkable for the fact that the voters rejected the constitutional proposals despite a favourable circumstances and media coverage for a “Yes” vote.

Debate on Australia’s constitution had been raging since the Double Dissolution election of 1975. It also coincided with the debate on Australia’s national identity through the decades. As Britain seemed destined for a “European future” (i.e. European Union membership), leaving the legacy of the Empire and Commonwealth behind, Australia was destined for an “Asian future” integrated into an Asia-Pacific economic bloc and weaking its historic relationships. The Commonwealth and the monarchy, it seemed, had lost relevance and the 1990s were certainly not kind to the Royal Family. The push for an Australian republic gathered momentum during the Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, and it seemed that such a change was inevitable.

The election of a Liberal government under John Howard in 1996 saw Australia’s debate and anxieties over national identity continue – Howard encouraged Australians to feel “comfortable and relaxed” about the nation’s history, as opposed to the increasingly fashionable progressive view that the nation’s foundation was an Original Sin. Unlike Keating and Hawke, Howard was in favour of Australia’s constitutional status quo but still committed to holding a constitutional convention in 1998. The convention revealed deep divisions among advocates for a republic, not least as to how a head of state was to be elected. Still, a referendum was to be scheduled for the following year.

Media coverage of the referendum campaign demonstrated an overwhelming bias in favour of a “Yes” vote for a republic, as former editor of Britain’s Daily Telegraph Lord Deedes noted:

“I have rarely attended elections in any country, certainly not a democratic one, in which the newspapers have displayed more shameless bias. One and all, they determined that Australians should have a republic and they used every device towards that end.”

The republic campaign received endorsements from many politicians, celebrities and businessmen, yet they could not paper over divisions in their own ranks over the constitutional model, undermining voters’ confidence.

The monarchist campaign for a “No” vote thus found itself in at a disadvantage in terms of resources and backing. Still mounted a brave and determined campaign through groups with dedicated volunteers such as the Australian Monarchist League and Australians for Constitutional Monarchy. One of the campaign slogans, “No to the Politicians’ Republic”, perfectly captured the cynicism many Australians felt towards the push for constitutional change, and towards the political class who they felt stood to benefit from it.

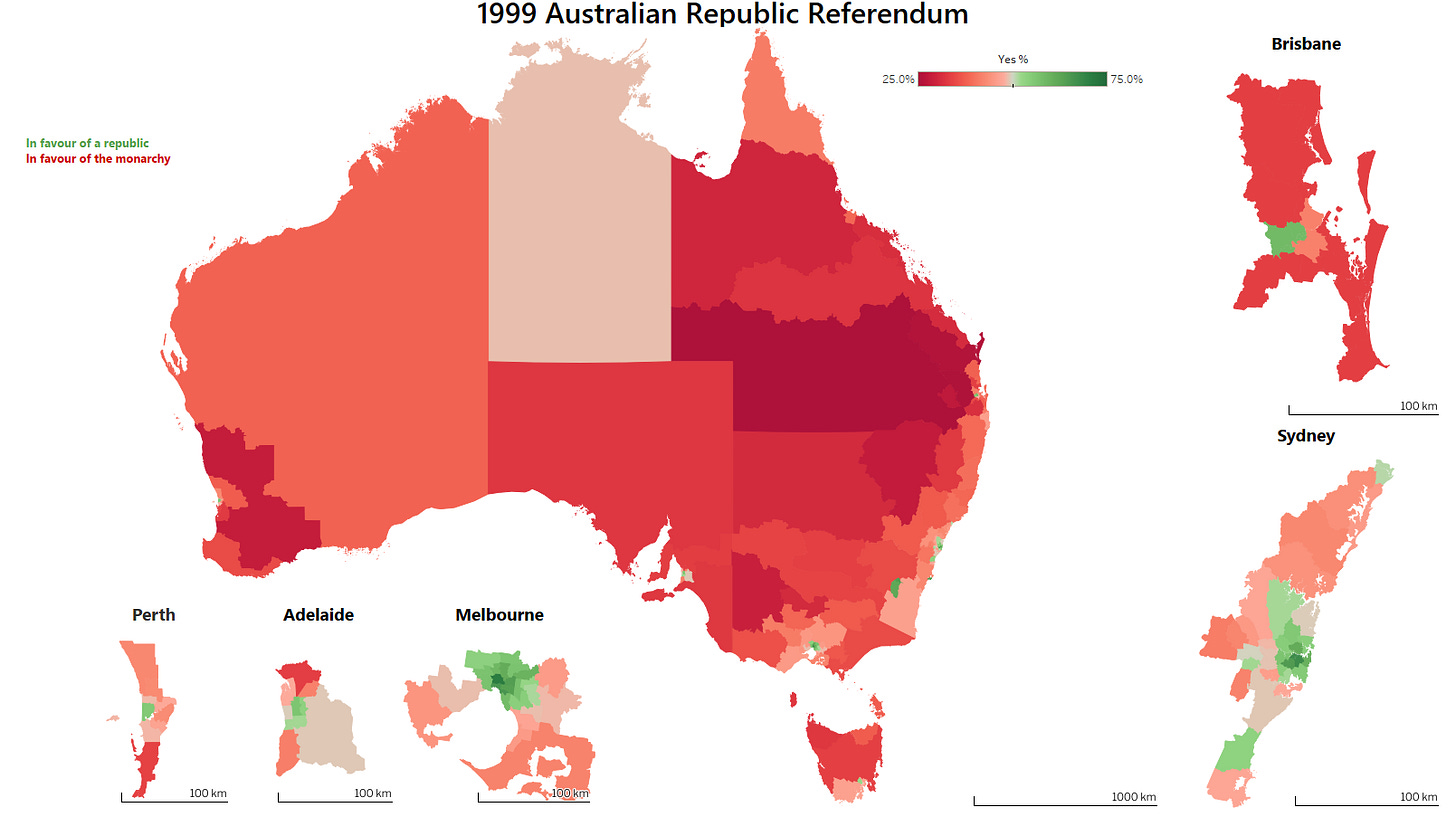

On the day of a referendum, Australian voters delivered a stunning result: the No side won 54.9% of the popular vote and won in all six states (in Australia, a referendum requires a majority in four states to pass). Tony Abbott, later to become prime minister, attributed the success of the monarchist campaign to the “healthy scepticism of the Australian people to change for change’s sake”.

While Australia has since had three prime ministers - Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard and Malcolm Turnbull - who are professed republicans, none of them made any serious moves to reopen the constitutional debate in Australia. In the last federal election, then Labor leader Bill Shorten made promises of a second referendum but failed to resonate with the voters. The Australian public appears to have no desire to revisit the republic issue. Even longtime republicans like Graham Richardson have conceded it is a lost cause.

But what lessons for today does Australia’s 1999 republic referendum? Firstly, that voters tend to be rather conservative on constitutional issues and are deeply sceptical about radical change. They feel that a change of the constitution and system of government will not make any difference to their day-to-day lives and see no reason to alter system which has served the nation so well. There is an inevitable cynicism about a push for “change” and “progress” for the sake of it.

The referendum outcome was not merely an endorsement of the monarchy and the constitution, but also an expression of cynicism towards the political class, media and celebrities who promoted a then fashionable cause. Australian voters believed they were not being told the whole story in 1999. Many even feared that the push for constitutional change was a mask for a more radical agenda to upend Australia’s traditions, values and governing structure.

Furthermore, the monarchist campaign in the referendum can provide valuable lessons and even inspiration for many movements, not least among American conservatives who may feel their campaigns face unfavourable circumstances and media coverage. Clear messaging coupled with hard work and dedication can go a long way, as it did for the “No” campaign in Australia in 1999.

It should also be noted that the republican cause in Australia was dominated at the top by members of the Baby Boomer generation, and the younger generations have either shown indifference to the issue or are even enthusiastic monarchists. A similar trend can be noted in Canada with the Quebec sovereignty movement, which similarly reached its peak in the 1990s.

Finally, the predictions that the monarchy and Commonwealth would lose all relevance in the 21st Century have not come to pass. Movements like CANZUK International keep the idea alive of closer links between Commonwealth nations which has gained traction following Britain’s Brexit vote, and the British monarchy in common with Europe’s other monarchies seem as secure (and popular) as ever.