Portugal's first republic - a failed experiment in elite progressivism

How Europe's first republic of the 20th Century showcased the fallacies repeated by today's progressive elitists

At the start of the 20th Century, the only republics in Europe were Switzerland, San Marino and France. Most of Europe’s monarchies, save for ten, fell during the 20th Century as a result of two World Wars. Almost never was this done by a popular vote, and almost never did it result in any improvement in the fortunes of nations concerned.

Such was the case of Portugal, the first European country in the 20th Century where a monarchy fell to a revolution. Following the Lisbon Regicide in February 1908 in which King Carlos I and his heir apparent Luis Filipe were assassinated, the young Manuel II came to the throne and would be the last king to reign in Portugal. Though they had parliamentary representation, the Portuguese Republican Party (PRP) had committed itself to establishing a republic by force, which succeeded in October 1910 with the help of sympathetic elements in the military.

The revolution and the republic that was born from it thus had a decidedly elitist character, given that the base of support for republicanism was among the elite in Lisbon and other major cities. Moreover, the Lisbon Regicide had set a gruesome precedent that would characterise the First Republic’s 16-year life, normalising political violence, intolerance and instability. While the new regime in Portugal sought and obtained international recognition, its international reputation would be very quickly tarnished by the character of the regime.

The republicans had divided among themselves not long after the revolution, between moderates and radicals. And while moderates such as Manuel de Arriaga and Antonio Jose de Almeida were elected as presidents of the republic, they were to be in a hapless position. The radical faction led by Afonso Costa (known as the “Democrats”) were dominant for much of the First Republic’s existence, yet were unable to provide stable or competent government.

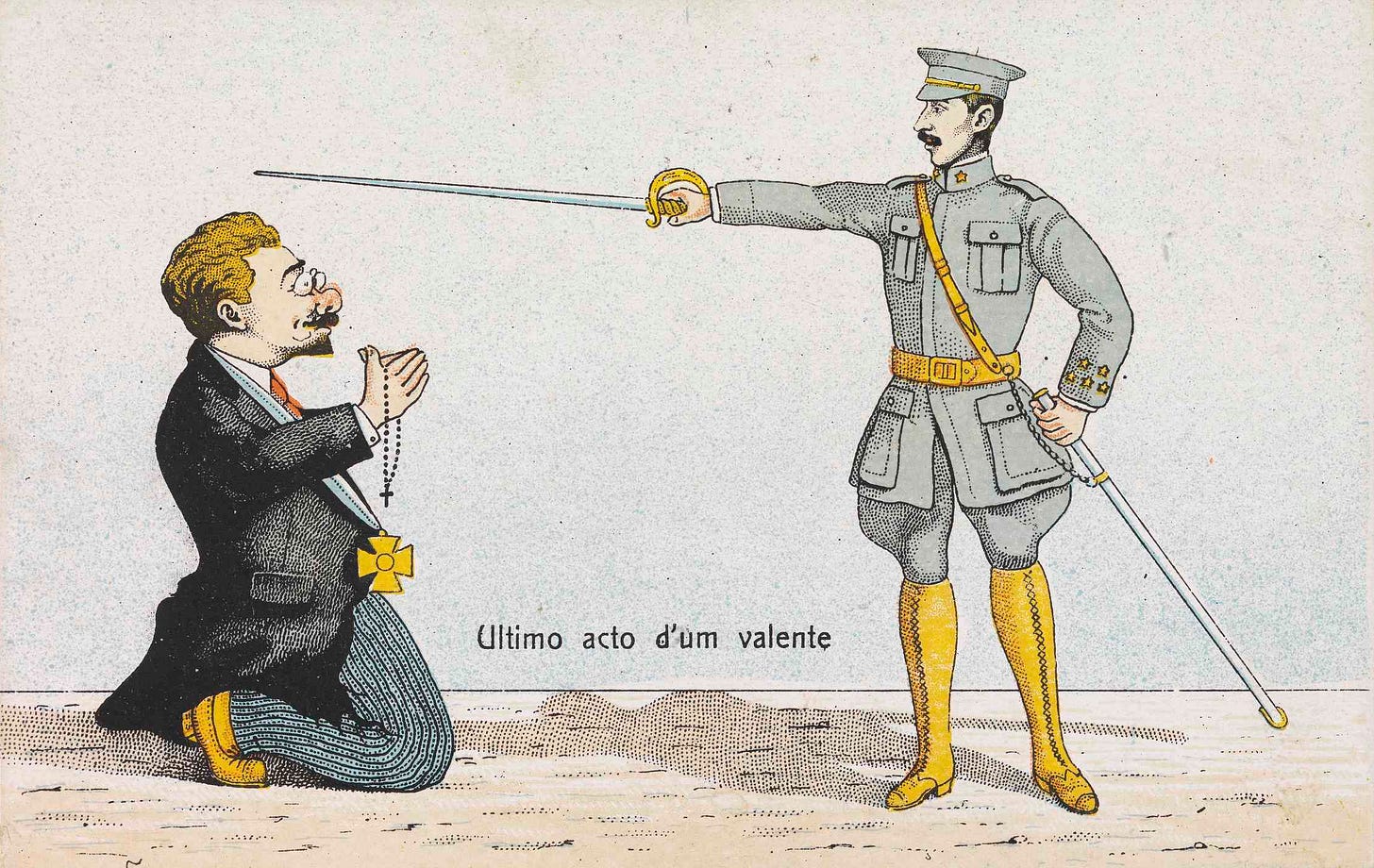

The new regime set about remaking the country in its own image, there was a new flag, anthem and currency. The radicals dictated the republic’s policy from the outset, with anticlericalism and persecution of the Catholic faith one of its central tenets. (The Fatima apparitions in 1917 took place against a backdrop of this hostile state policy). They enacted measures to effectively exclude monarchists from political life, and even went as far as to restrict voting rights perhaps because they looked down on the “deplorables” of the time (i.e. monarchists and the Catholic faithful, and even more moderates republicans).

This is because the radical republicans, neither liberal nor democratic, believed that the republic and thus the country belonged to them. Ideological purity was emphasised: moderates were seen as traitors to the cause for daring to deviate, if they were inclined to show tolerance towards Catholics and monarchists, let alone work with them.

The full range of tactics we commonly associate with today’s woke ideology and cancel culture were deployed in the First Republic - censorship, harassment and intimidation of political opponents and the media. Resistance against the new regime was inevitable in such a hostile environment, and monarchists attempted insurrections while the military would come to be involved in politics. Furthermore, the “Democrats” had their own group of thugs to attack opponents known as Formiga Branca (“White Ant”), a precursor to Antifa. (However, during the First Republic, Marxist and anarchist movements were weaker in Portugal than elsewhere in Europe, e.g. Spain).

Portugal’s international reputation was sullied by a regime which claimed to be based on “enlightened” republican ideals, but was in fact demonstrating characteristics of a dictatorship. The treatment of political prisoners was scandalous and drew attention abroad, with protests by the Duchess of Bedford and Arthur Conan Doyle raising awareness outside Portugal.

I should note that although the progressivism of the era had many of the features of today’s progressivism, it was far from “woke” as we understand it today. The First Republic did not advance women’s rights (women only gained the vote under the Salazar regime) or labour relations, or radically alter the structure of Portuguese society and economy. Furthermore, the republic was committed to maintaining its colonial empire - Portugal being the last European nation to divest itself from having an empire.

Military involvement in Portuguese politics, of which there was a long history, manifested itself in uprisings and coups, and the ascension to power of more conservative military officers in Joaquim Pimenta de Castro in 1915 and Sidonio Pais in 1917. Both of these regimes were considered to be dictatorships, but they represented a conservative backlash against the radicalism and intolerance that came to characterise the First Republic.

The short-lived regime of Pimenta de Castro, appointed by President Arriaga in January 1915 and lasting only four months, made significant policy changes that alarmed radical republicans. The new government allowed monarchists to organise openly, their civil rights being restored, while there was some change in the official policy on religion. Pimenta de Castro was brought down by a revolt in May, but the restoration of “normal” republican government did not bring about an improvement in the political or social situation.

As political instability and social unrest continued, Portugal’s involvement in World War I contributing, Sidonio Pais came to power in a coup in December 1917, supported by opponents of Afonso Costa and his “Democrats” (PRP). His regime, lasting only a year, has been seen as a prototype of authoritarian “strongman” regimes seen in the 20th Century. He certainly moved to consolidate power (e.g. the offices of President and Prime Minister) in his hands, yet at the same time, his policies had considerable public approval, especially from more conservative sectors of the population.

Sidonio Pais tried to ease church-state tensions (this was following Fatima), and monarchists once again were able to operate more freely in Portugal. He held elections with a much wider electoral franchise than previously, and Catholic and monarchist representatives were elected to Parliament.

In December 1918, just as World War I ended in Europe, Sidonio Pais was assassinated by a radical activist. The assassination was a critical blow to the First Republic: firstly, it ended any prospect of political stability being achieved, secondly, coming over a decade after the Lisbon Regicide it represented the pattern of political violence that was normalised.

Because the First Republic was never accepted by a significant portion of the Portuguese population who remained loyal to the deposed monarchy, and because of the regime’s political and religious persecution campaigns, it was not surprising that there would be resistance and revolts.

The redoubtable monarchist Henrique de Paiva Couceiro had attempted a number of monarchist risings after the revolution, and the aftermath of Sidonio Pais’ assassination was to create the optimal conditions for the biggest monarchist uprising of the First Republic period.

Northern Portugal has long been a bastion of conservatism and monarchism, its economy dominated by smallholders. It was there that the uprising, known as the Monarchy of the North, took place in January 1919, when monarchists proclaimed the restoration of the Kingdom of Portugal in Porto, and lasted a month. While unsuccessful, it demonstrated the volatility of the political situation and the possibility of civil war. Monarchist sentiment in Portugal never died out, and the movement remains active today.

However, restoring the “old” Republic after the Sidonio Pais regime and the “Monarchy of the North” did not result in stability or peace being restored. The moderate republicans would coalesce into a new opposition party, the Liberal Republican Party (PLR) who in 1921 managed to win an election with Antonio Granjo becoming Prime Minister - the only time the radicals of the PRP did not win an election.

Less than two months after taking office, the new government faced a revolt involving elements of the GNR (the military police force which was in fact a highly politicised praetorian guard). In what was to be known as the Noite Sangrenta (“Bloody Night”), Granjo along with one of the founding fathers of the Republic, Antonio Machado Santos, were assassinated. The killings deepened Portugal’s political turmoil, and were just the latest episode of normalised political violence which began with the Lisbon Regicide 13 years earlier.

The fate of First Republic was effectively sealed at this point, but it was not until five years later in May 1926 that a successful military coup overthrew the constitutional order and established what was to be one of Europe’s longest-lasting dictatorships. That there wasn’t much resistance to the coup reflected the low regard for the system among great swathes of the populace.

As the first overthrow of a monarchy in 20th Century Europe, Portugal should have offered a cautionary tale to the continent. The First Republic was to prove a disastrous experiment by virtue of its elitist radicalism, sectarianism and exclusivism. The radical republicans treated the state and the nation as its own personal possession, resorting to lawless means (corruption, censorship, arbitrary imprisonment and street thuggery) to maintain their grip.

The Original Sin of the Republic was the Lisbon Regicide, which set the tone for normalising violence as a political instrument over the next two decades. The Spanish Republic established in 1931 was not only to repeat its errors, but magnify them with polarisation and violence reaching even greater ferocity with even moderates and liberals becoming targets of the Left. This led to a Civil War characterised by brutality and atrocities being committed by both sides.

In Portugal, serious attempts at pushback in Portugal from moderates and conservatives (1915, 1917-19 and 1921) triggered a violent reaction from radicals and their supporters. However, political violence and terror in the First Republic (1910-26) and transition (1974-76) periods seemed not to go beyond certain limits in stark contrast to the Spanish Republic and other examples where there were far more victims of political violence (this is not to mitigate the impact of such occurring).

Both Portuguese and Spanish republic bore little resemblance to their American counterparts, and fell short of the standard for liberal democracy and rule of law. Yet today’s progressives appear determined to repeat the disastrous experiments of Spain and Portugal in terms of remaking the state and society in their own image. They are even utilising many of the same methods, and underestimate the potential for a backlash.

Neither did the First Republic resolve Portugal’s underlying social and economic issues since the 19th Century, something both sides of the political spectrum actually agree on. As mentioned above, Portuguese “progressivism” with its elitist character did not create a more egalitarian society or change its social and economic order. Somewhat ironically, the conservative authoritarian regime that replaced the First Republic made at least a modicum of progress on some issues, whether it was the enfranchisement of women or attempting to get the nation’s finances in order.

As I will explore in my next piece on Portugal, this would not be the last time the attempt to advance a radical agenda would be met with an attempted pushback.